The Inflation peak is in. But that doesn’t mean rate hikes are done.

Last summer’s British heat wave was an excellent example of what behavioural economists tend to call recency bias, or the tendency of people to over fix on recent experience. After a few days of temperatures rising about 30 degrees Celsius, more than a few people found themselves looking at the forecasts and thinking “it’s only going to be 25 degrees today, that is much cooler”. Whilst there is no doubt that 25 degrees feels cooler than 30, there is also no doubt that 25 degrees, in British terms, is an objectively hot day. Only the experience of the most dramatic heatwave in decades made it feel cool.

Something similar is now happening with inflation. Whilst the annual rate of change in prices is decelerating materially across the developed economies, it remains much higher than has been normal for the past few decades.

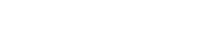

US inflation, the global bellwether, fell to a 15 month low in the most recent data. US experience, so far at least, has worked reasonably well as a roadmap for other advanced economies. The first country to recover, economically at least, from the pandemic was also the first to experience a post-pandemic surge in prices.

source: SORBUS PARTNERS, Federal Reserve Economic Data (data as at: 15/02/23)

Eurozone inflation has fallen to an eight month low of 8.5% and the UK’s rate of price changes is now at a five month low – although still over 10%.

Much of this represents global factors. Energy prices are dramatically off their highs. A barrel of oil is trading around $80 today against over $90 a year ago and summer peak of over $120. Given inflation measures the annual change in prices then, unless the cost of energy soars in the coming months, energy price disinflation should drive the headline rate of inflation down over the coming months.

Global supply chains too are in much better shape than this time last year. The slow but steady recovery from the disruption of the pandemic has been given a further fillip by China’s abandoning of its zero-covid policy of rolling sudden lockdowns.

There is also little doubt that the sharp rises in interest rates experienced over the past year are beginning to be felt. Higher borrowing costs and tighter financial conditions are helping to take some of the heat out of economic growth and relieve price pressures.

But recency bias is something to guard against. Whilst they may be lower than a few months ago, US inflation at 6.4%, Eurozone at 8.5% and UK at 10.1% are all still at levels which would have been almost unimaginable just three years ago.

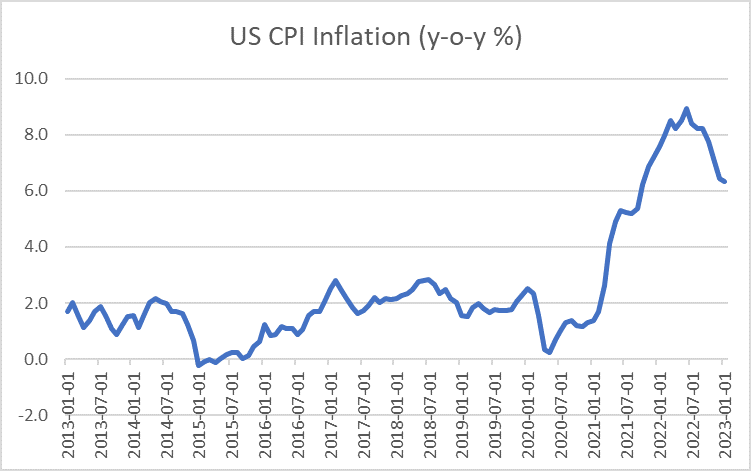

A closer look at the breakdown of British inflation usually illustrates why now is not yet the time to feel too much relief.

source: SORBUS PARTNERS, Office for National Statistics (data as at: 15/02/23)

Goods price inflation – mostly a story of energy costs and global factors – remains extremely high but should drop sharply in the months ahead. A look back at the past decade clearly shows that such inflation is a volatile series.

More worrying for policymakers is services price inflation. This sort of inflation is predominantly a story driven by domestic factors – and in particular by developments in the jobs market. Whilst it too has come down from its highs it remains some 2-3x higher than the pre-pandemic level.

Services price inflation tracks closely with core inflation (inflation excluding the more volatile components such as food and energy prices). It is uncomfortably high core inflation that has pushed the Bank of England into its steep tightening cycle and the news here is less good.

The most recent data shows core inflation falling from an annual rate of 6.3% in December to 5.8% in January, a larger drop than expected by forecasters but still at a deeply unpleasant level for Threadneedle Street. In the decade before the pandemic core British inflation averaged just 1.8%.

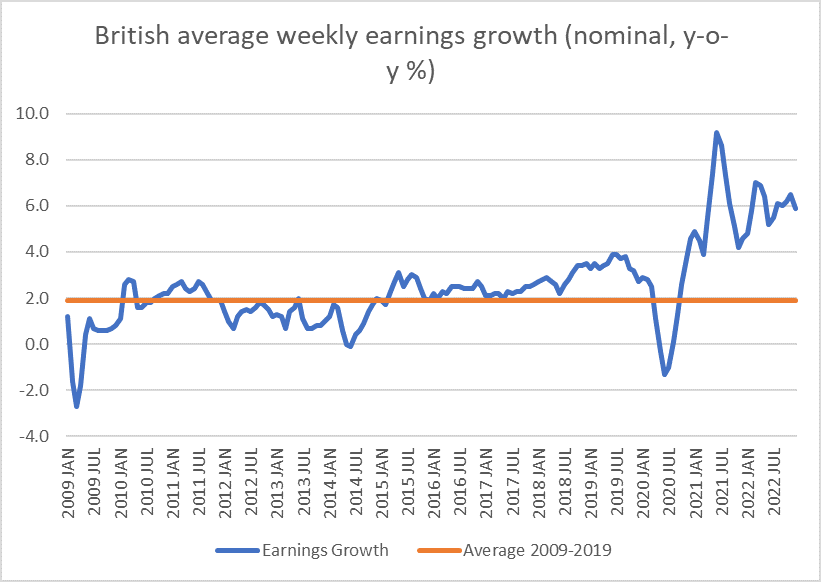

It does not take long to see what is maintaining it so stubbornly high. Wage growth, in cash terms, remains high.

source: SORBUS PARTNERS, Office for National Statistics (data as at: 15/02/23)

The British jobs market seems to have somehow contrived to give the economy the worst of all possible worlds. Wage growth is noticeably below the level of headline inflation and so households are experiencing a sharp fall in their real income and seeing their living standards decline with an unpleasant knock on impact on consumer spending and firms. And yet it remains high by recent experience, adding to the cost base of firms and pushing them towards larger price rises.

This is the bind the Bank of England finds itself in. Lower energy costs and improved supply chains should see goods price inflation falling sharply over the course of 2023. It is far from impossible that goods price inflation actually falls below by the Autumn. That should be enough to keep headline inflation falling almost as fast. But as long as services and core price inflation remains above 4% then any relief will prove transitory. Once goods prices eventually find a level then headline inflation will begin to rise again. To defeat inflation, the Bank needs to bring down service price inflation and that means slowing the jobs market further.

In other words, the good news of recent months on the inflation front does not mean that the current hiking cycle is finished.

That said, the better global inflation dynamics – and the rapid switch in the stance of fiscal policy to a more restrictive approach – have made the Bank’s task easier.

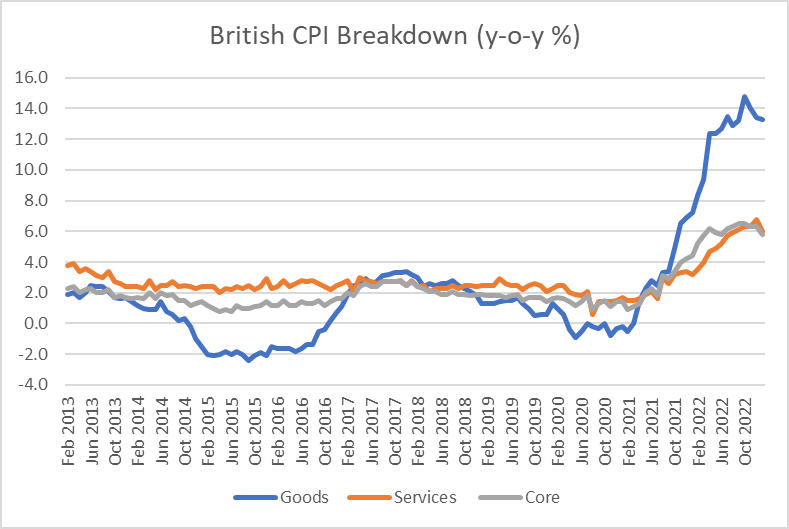

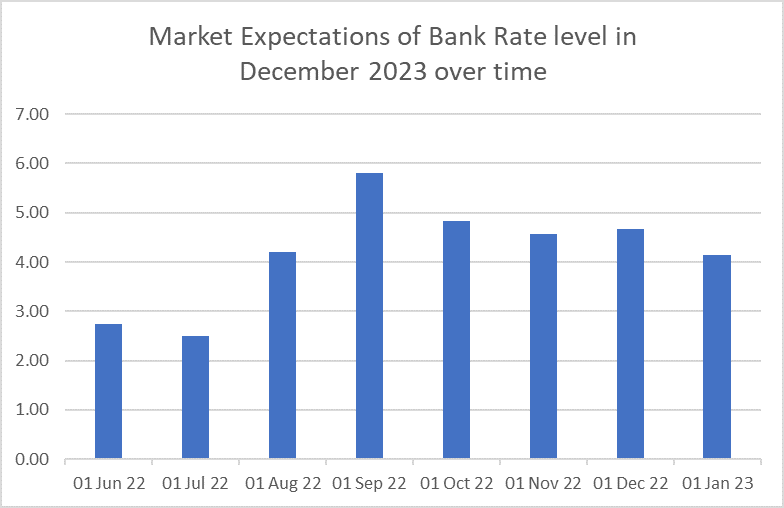

The best way to get a sense of the changing likely path of the Bank’s monetary policy is to look back at where financial markets expected Bank Rate to reach by December 2023 since last summer.

source: SORBUS PARTNERS, Bank of England OIS curve data (data as at: 15/02/23)

Back in June last year, markets expected Bank Rate to reach just 2.75% by the end of this year (then 18 months in the future). The surge in energy prices last summer, coupled with the short lived Truss government’s abandonment of fiscal probity and promises of large tax cuts, saw expectations of Bank Rate pushed up 5.8% by last September. Since then expectations have drifted back down to something between 4% and 4.25% by the end of this year with a peak of 4.5-4.75% this summer.

So whilst the worries about interest rates being around 6% proved fleeting, the painful reality is that interest rates are likely to stay above 4% for quite some time to come. Recency bias may make 4.5% feel “not as bad as 6%” but 4.5% is still well above the sub-1% that characterised the 2010s.

The big global picture is that the peak in inflation is now in the rear-view mirror and fears of interest rates reaching the kind of levels not seen since the early 1990s is probably also in the past. But equally importantly even if inflation does continue to fall this year – driven by global developments in goods markets and arithmetic – it still seems likely to be uncomfortably high for both firms and households and further rises in interest rates remains the base case. So while the peak in inflation is to be welcomed, we are far from the end of the story and it is much too early to conclude that everyone will live happily ever after.

What we are watching in the next month:

Friday 24th Feb, British consumer confidence. To understand the British economy, the best advice is to ignore the forecasts of economists and focus on what consumers are saying. The GfK measure of consumer confidence – which dates back to 1974 – may begin to show some signs of recovery this month against a backdrop of slower price rises. But it is also likely to remain at levels showing a pullback in consumer spending.

Thursday, 2nd March, Eurozone data. Early March sees the release of both unemployment and inflation data for the Eurozone. Inflation dynamics in Europe have been driven more by energy price moves than developments in the domestic labour market compared to the UK or US. Indeed it would be no surprise if European inflation was to fall below US inflation by the end of the year. That should give the European Central Bank some space to tighten less aggressively than its peers in the months ahead. Tuesday, 7th March, Australian Interest Rate decision. For all the focus on the big central banks – the US Fed, the ECB, the Bank of England and the Bank of Japan – the Reserve Bank of Australia is worth keeping an eye on. It has raised interest rates at its last nine meetings but March may see a pause. Global developments impact quickly the relatively small and very open Australian economy and watching how its central bank responds provides clues as to how others will move in the future. If the RBA feels able to pause its tightening this Spring, expect others to follow by the Autumn.